- Sep 6, 2024

The Scientists of the Manhattan Project

- Aerin C and Vaishnavi P

- Physics

- 0 comments

The Manhattan Project was the secret WWII US military research project that created the world’s first atomic bomb. It all started when Hahn, Strassman and Meitner discovered nuclear fission. Many scientists around the world saw the potential of the huge energy released and quickly began working on a weapon that could defeat the enemy.

The name of the Manhattan Project originated from Columbia University in Manhattan District, where the original research had been done. Leslie Groves, Brigadier General, was in charge of the bomb’s creation and research, together with thousands across the USA they created the instrument that ended WWII. In total there were three main sites involved with the creation of the atom bomb: Hanford, Washington; Los Alamos, New Mexico; and Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

In Tennessee, Oak Ridge was an industrial complex built to enrich uranium, increasing the concentration of uranium 235 from uranium 238. The Hanford, Washington site was mainly created to produce plutonium, it was only up to mid-1945 enough uranium and plutonium were available for a bomb. Los Alamos, New Mexico was the site of the many precise calculations and experimentation that created the specifications of the bomb. Nearby the area was the Trinity Test Site, evidence of the first human caused nuclear explosion.

More than 500,000 people contributed to the project, including scientists, engineers, chemists, political leaders and more. Meet the visionaries behind this critical starting point in scientific history that started the nuclear age. This article will examine a few of the main scientists and discuss the implications of the nuclear age that began.

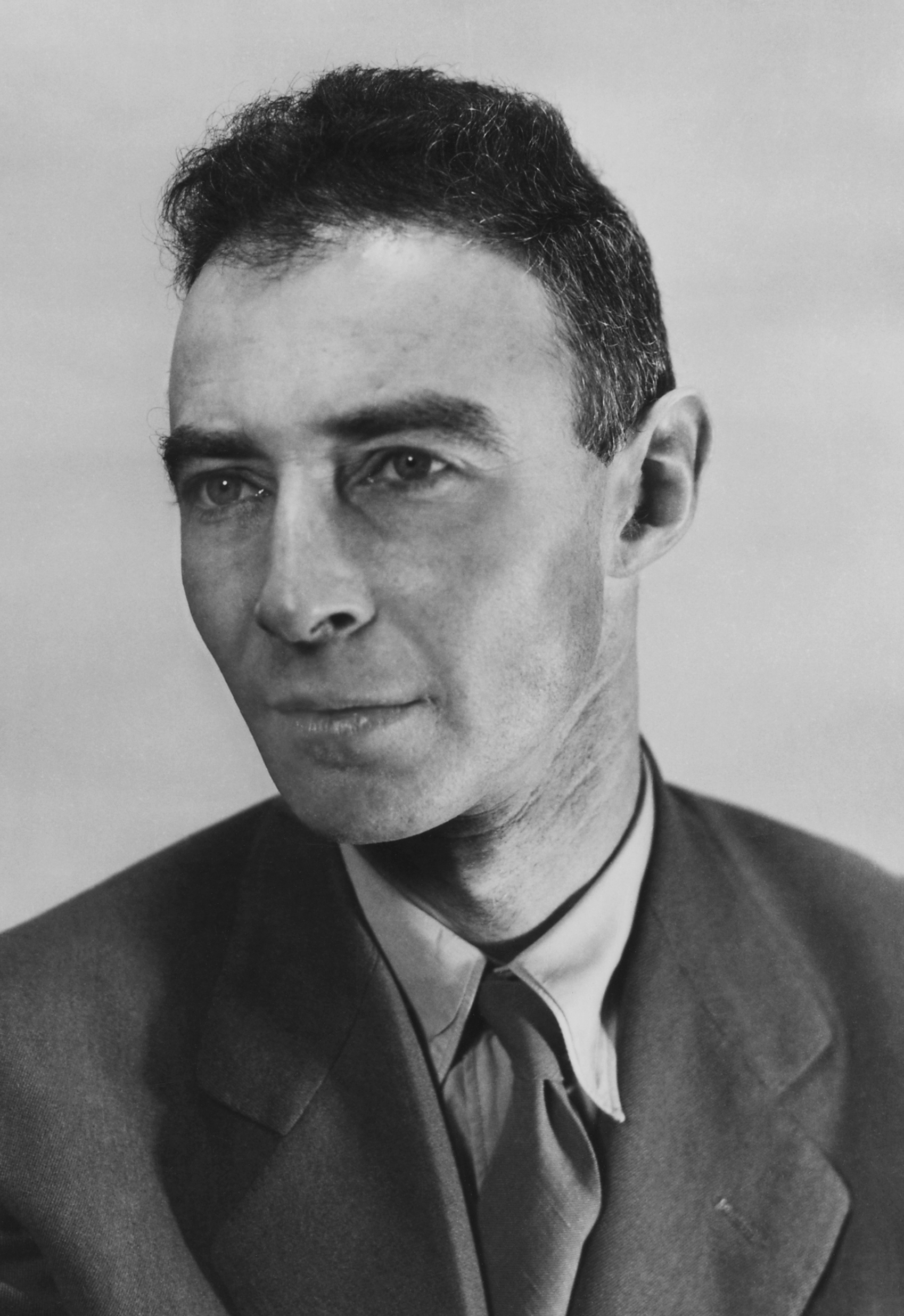

Robert Oppenheimer

Julius Robert Oppenheimer or J. Robert Oppenheimer was a lead scientist on the Manhattan Project, even accredited to be the father of the atom bomb. He was born in New York City and showed immense scientific aptitude like invitations to lecture at the New York Mineralogical Club at twelve and attending Harvard University. Under the tutelage of Ernest Rutherford at the Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge in 1925 he worked with the British scientific community to work on atomic research. Later on, he was invited by Max Born to the University of Gottingen, where he received his doctorate in 1927 and met many other famous physicists like Bohr and Dirac. Oppenheimer’s ranged from particle physics (electrons and positrons) to astrophysics (blackholes and neutron stars) and quantum mechanics.

In the 1930s to 40s, Oppenheimer was researching neutrons, this made his capabilities very suited to become a scientific director of the Manhattan Project. While guiding many other scientists he formulated the logistical calculations needed to extract enough radioactive materials for the bomb as well as creating methods for implosion.

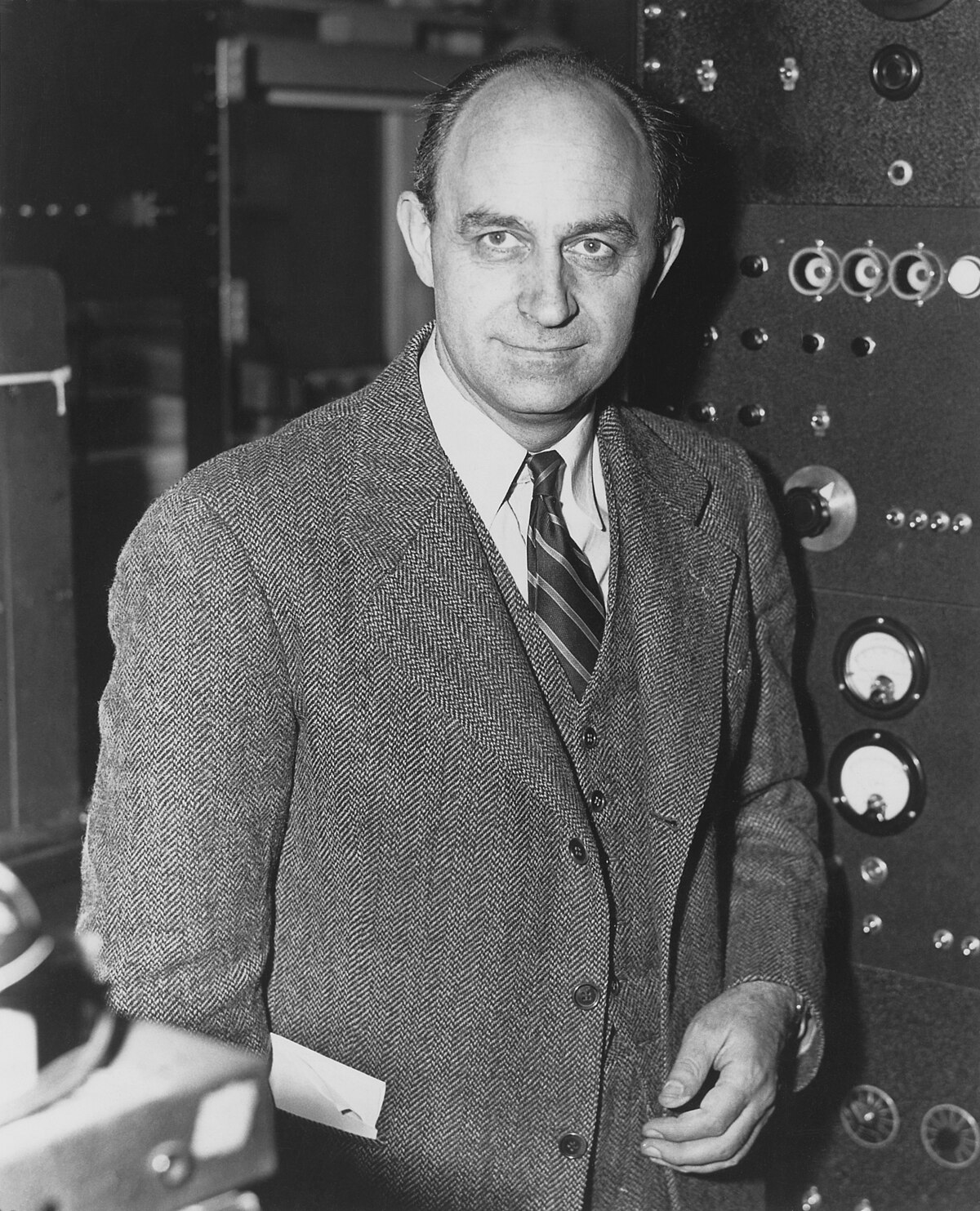

Enrico Fermi

Fermi, an Italian-American physicist famed for many things: fermions, Fermi statistics, the Fermi paradox, responsible for the first controlled nuclear chain reaction on a sports field underneath the Chicago stadium and a contributor to the Manhattan Project. He graduated with a doctorate from the University of Pisa, a special higher education place for gifted students. Like Oppenheimer, Fermi spent several months with Max Born in Gottingen on an Italian government scholarship before lecturing Mathematical Physics and Mechanics at the University of Florence.

Through the 1920s, Fermi pioneered various statistical laws that governed particle physics and spent lengthy periods investigating beta decay through theoretical physics. Those discoveries would be awarded by the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1938. To escape the dictatorship of Mussolini, Fermi moved to the United States and took up a professorship at the University of Columbia in 1939. During that time, Bohr also arrived with news of nuclear fission, hence Fermi and a group of researchers determined that a chain reaction in uranium made it powerful enough to create a large, dangerous explosion. But it proved to be difficult to separate U-235 (uranium 235) and the group was stumped. After Seabort’s discovery of plutonium, an element with a higher probability of fission, Fermi met with Arthur Compton and under the Stagg Field football stadium, they put together CP-1 (Chicago Pile 1), which successfully released a sustained chain reaction.

Fermi did follow up research on CP-2 and CP-3, before becoming more involved with the Manhattan project at the Los Alamos laboratory. He later became associate director at the lab and had a F-Division (the Fermi Division) established. The Water Boiler reactor, which experimented with the first boiler nuclear reactor or the thermonuclear device, which led to the development of the H-bomb(hydrogen bomb) later on.

Albert Einstein

Einstein, one of the most recognisable scientists around the world, famous for the theory of special relativity, theory of general relativity, the photoelectric effect and his Annus Mirabilis paper on the Brownian motion. He wrote a letter to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on behalf of Leo Szilard to warn the United States of the German threat on the world with their own atomic bomb in the making. The progress between 1940 and 1941 was slow but the government officially launched the project in late 1941. However, due to Einstein’s pacifist tendencies, he was denied clearance to work on the Manhattan project. It was recorded that he was full of sadness after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and remained remorseful of his associations with the destruction and harm of the bomb.

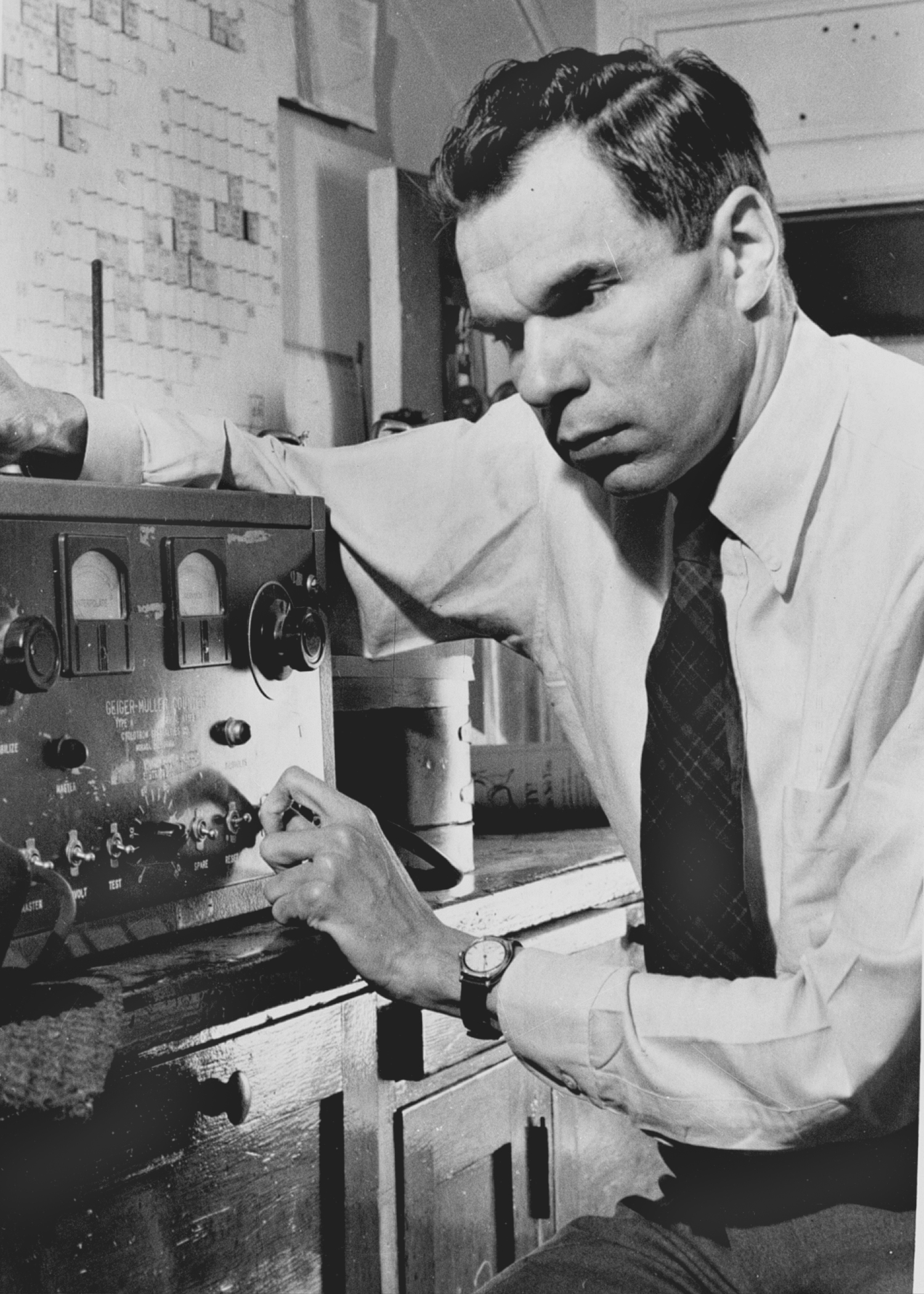

Leo Szilard

Szilard was a Hungarian-American physicist on the Manhattan Project team. He drafted the letter to President Roosevelt urging him to place importance on nuclear research; however, remained deeply suspicious of the military intentions entwined in the project, even requesting the bomb never to be dropped on Hiroshima. Szilard worked at the Met Labs with Arthur Compton and Fermi on the nuclear reactors, and worked on the Manhattan Project over the course of the war.

Szilard was also a contributor to the Franck report, a report that outlined the possibilities of the nuclear arms race and the emphasis on a non-combat demonstration of the atomic bomb instead of the plan for Hiroshima. There was another petition in July 1945 urging the government not to use the bomb but it failed. After the war, Szilard moved towards biophysics and pioneered disarmament and nuclear safety, deeply regretful of the implications of what he had contributed to the world.

Glenn Seaborg

Seaborg was a chemist that discovered plutonium, the fuel of Fat Man that was dropped on Nagasaki in 1945. The discovery of plutonium started when Seaborg bombarded uranium with deuterons (heavy hydrogen composed of one proton and one neutron), it created plutonium 239, a better alternative to the U-235. Similar to Szilard, he worked on the Franck Report as a committee member and played a role in the development of nuclear science and policy. He was part of the Atomic Energy Commission and continued discovering various elements such as seaborgium, curium, californium and more.

A conclusion

The atomic bombs were one of the factors that contributed to the Cold War arms race between the Soviet Union and the United States of America. Each nation was working towards one-upping each other for over 40 years in an intense ideological rivalry, unfortunately threats of total nuclear destruction overshadowed the collaborative successes experienced by the group of scientists. The consequences of the bomb were horrific in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, creating a legacy of destruction that still lingers around the world today. Today, nine countries around the world have nuclear weapons, this includes: the USA, China, Russia, North Korea, Israel, Pakistan, India, France and the UK. Together, they have 13,000 nuclear warheads in stock. Despite the immense scientific progress and achievement from the Manhattan project, it unearthed an ethical debate on how one uses the knowledge they have and the power of scientific discovery. Let it be a reminder of the cost of knowledge and the power each discovery holds but also a reminder the preservation of humanity should prevail regardless.

References

“Albert Einstein – Biographical.” NobelPrize.org, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1921/einstein/biographical/. Accessed 24 August 2024.

da Vinci, Leonardo. “Manhattan Project | Definition, Scientists, Timeline, Locations, Facts, & Significance.” Britannica, 22 July 2024, https://www.britannica.com/event/Manhattan-Project. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Einstein and the Manhattan Project | AMNH.” American Museum of Natural History, https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/einstein/peace-and-war/the-manhattan-project. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Enrico Fermi – Biographical.” NobelPrize.org, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1938/fermi/biographical/. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Enrico Fermi | Biographies.” Atomic Archive, https://www.atomicarchive.com/resources/biographies/fermi.html. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Enrico Fermi - Nuclear Museum.” Atomic Heritage Foundation, https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/profile/enrico-fermi/. Accessed 24 August 2024.

Howell, Elizabeth, and Ailsa Harvey. “Albert Einstein: His life, theories and impact on science.” Space.com, 18 November 2022, https://www.space.com/15524-albert-einstein.html. Accessed 24 August 2024.

Kennedy, Joseph, and Arthur Wahl. “Manhattan Project: People > Scientists > GLENN T. SEABORG.” OSTI.GOV, https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/People/Scientists/glenn-seaborg.html. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Leo Szilard - Nuclear Museum.” Atomic Heritage Foundation, https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/profile/leo-szilard/. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Manhattan Project: Events.” OSTI.GOV, https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Events/events.htm. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Manhattan Project - Manhattan Project National Historical Park (U.S.” National Park Service, 28 June 2024, https://www.nps.gov/mapr/learn/manhattan-project.htm. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Manhattan Project: People > Scientists > ENRICO FERMI.” OSTI.GOV, https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/People/Scientists/enrico-fermi.html. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Manhattan Project: People > Scientists > LEO SZILARD.” OSTI.GOV, https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/People/Scientists/leo-szilard.html. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Manhattan Project Scientists: Glenn Theodore Seaborg (U.S.” National Park Service, 11 January 2023, https://www.nps.gov/people/manhattan-project-scientists-glenn-theodore-seaborg.htm. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Manhattan Project Scientists: Leo Szilard (U.S.” National Park Service, 26 September 2023, https://www.nps.gov/people/manhattan-project-scientists-leo-szilard.htm. Accessed 24 August 2024.

Perfas, Samantha Laine. “Oppenheimer, a complicated man — Harvard Gazette.” Harvard Gazette, 19 July 2023, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2023/07/closer-look-at-father-of-atomic-bomb/. Accessed 24 August 2024.

Qvale, Miles. “Bohr's Exile And The Atomic Bomb.” The Journal of Young Physicists, 8 October 2023, https://www.journalofyoungphysicists.org/post/bohr-s-exile-and-the-atomic-bomb. Accessed 24 August 2024.

Rouzé, Michel, and Anna Dubey. “J. Robert Oppenheimer | Biography, Manhattan Project, Atomic Bomb, Significance, & Facts.” Britannica, 1 August 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/J-Robert-Oppenheimer. Accessed 24 August 2024.

Schweber, Silvan. “Max Born | Nobel Prize Winner, Quantum Mechanics Pioneer.” Britannica, 9 July 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Max-Born. Accessed 24 August 2024.

“Scientists - Manhattan Project National Historical Park (U.S.” National Park Service, 4 April 2023, https://www.nps.gov/mapr/learn/historyculture/scientists.htm. Accessed 24 August 2024.