- Oct 25, 2024

Hooked On Molecules: The Chemistry of Addiction

- Arjun B and Ahmad S

- Chemistry

- 0 comments

Pleasure. The one thing all humans strive for. Some find it in art, some in food, others take more adventurous routes through substances like drugs and alcohol. While the sources of our pleasure may be different, the route they take to our brain is quite similar.

Each of these activities act as triggers for the human brain to start releasing neurochemicals that amplify and facilitate this feeling of pleasure in all of us. Parts of the brain linked to the release of neurochemicals such as dopamine and serotonin include the substantia nigra area, the ventral tegmental area and hypothalamus. [Arbor, 2010] [Sayin, H.U.,] The three regions of the brain have been extensively studied for their links to dopamine production and this feeling of pleasure. To make life easier, scientists named these hotspots of the brain the “reward centre”.

Now, back in the Stone Age, the reward centres were primarily focused towards survival. For example, the hyperactive mesolimbic dopaminergic system leads to an increased incentive for food and the substantia nigra is the site of sexual pleasure, encouraging reproduction. However, the once-evolutionary imperatives, driving forth the life of early humans are now at arms reach.

Humanity has progressed. We no longer need dopamine to influence our survival, thankfully we have become slightly smarter - for the most part. Yet, we still have it. We can still feel it. Why is that, you might wonder? Well, these reward centres in our brains are plasticised rather than fixed. This means they can change over time. Even a once-beloved sweet taste can become unpleasant in some circumstances even though the taste itself has not changed. [Arbor, 2010]. Furthermore, long-term plasticity in limbic structures in the reward centres might reflect enduring motivation changes, arousal, food preferences, etc, showing that these dopamine-releasing sources are still key to the development of the brain. [Berridge & Kringlebach, 2008].

This leads us to addiction. Addiction is described by Oxford Dictionary to be a state of dependence produced by either the habitual taking of drugs or by regularly engaging in certain behaviours. The three cups of coffee that get us through the day or the occasional smoke break after the shift are still signs of addiction and with the advent of technology in the 21st century, we see pocket-sized devices become a source and centre of our addictions.

An addiction forms from the activation of the brain’s reward system; but get this, alcohol and drugs emulate the increase in dopamine triggered by phasic dopamine firing, firing frequency of dopamine associated with rewarding stimuli.

This release has shown to positively reinforce further use of the substance and increase the likelihood of repeated use. A second sub-region of the basal ganglia, the dorsal striatum, is involved in habit formation. The release of dopamine and release of glutamate (a neurotransmitter which regulates dopamine release) can trigger changes in the dorsal striatum. These changes strengthen substance-seeking and taking habits, ultimately contributing to compulsive use. [Koob,G.f & Volkow, N.D (2016,August)]

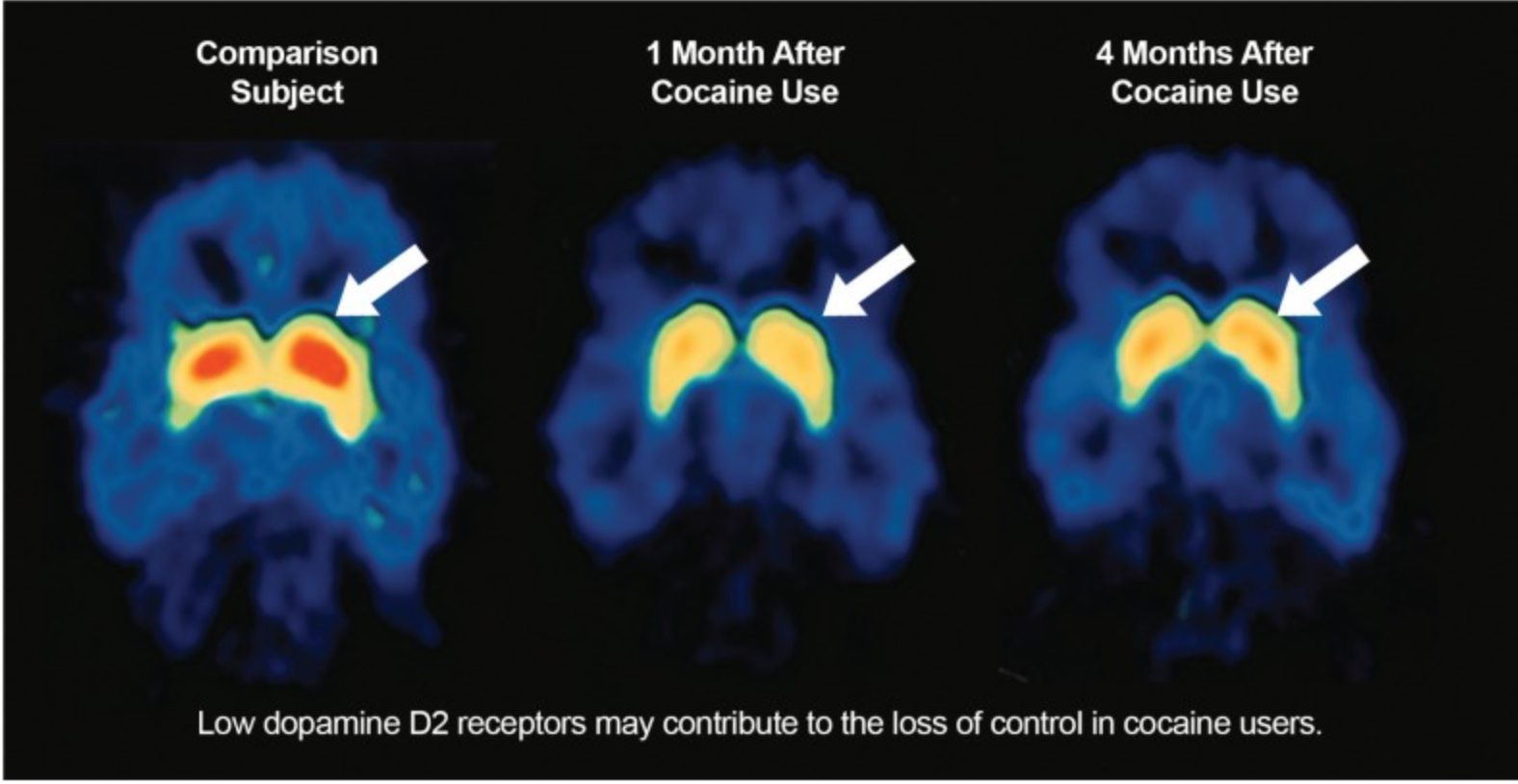

Over the long-term, all substance abuse causes dysfunction in the brain's reward system. For example, brain imaging studies on individuals with substance abuse addictions have consistently shown long-lasting decrease in the D2 Dopamine receptor. Further studies have shown that a certain stimulant will cause a smaller release of dopamine in an individual who is addicted compared to someone who is not.

These findings allow us to conclude that people with substance-related addictions experience an overall reduced sensitivity of the brain reward system, both to addictive substances and natural reinforcers, such as food or sex. This reinforces their prolonged use of the substance as they become dependent on it to produce enough dopamine to feel pleasure or satisfaction, as they may otherwise not be able to in their everyday life. [Koob,G.f & Volkow, N.D (2016,August)]

So, how can we treat addictions? To successfully treat a patient’s addiction, we must also treat their withdrawal. When patients first stop using drugs, they can experience various physical and emotional symptoms, including depression, anxiety and other mental health conditions.

[US.DHHS, (Sep 25, 2023)] Certain medications such as Buprenorphine for moderate and severe opioid withdrawal because it exhibits high-affinity binding to mu-opioid receptors, preventing withdrawal symptoms and cravings. Kumar, R. (2024, June 8)

Another way of treating addiction is through behavioural therapy. This could include cognitive-behavioural therapy, contingency management or motivational enhancement therapy, helping individuals modify their attitudes related to drug use. As a result, patients are able to handle stressful situations and various triggers which may cause a relapse.

What does the future hold in terms of treatment for addiction? It seems that AI is developing faster than we blink because it won’t be long until AI-driven addiction care becomes a viable treatment. In the not-so-distant future, AI may function as a therapist, predict outcomes of addiction treatments, and may soon be able to summarise medical records. There are also ongoing trials which may prove beneficial in providing pharmacological treatments which may prove effective against the withdrawal of certain substances.

As we continue to develop our understanding of addiction, it's clear that addiction does not have a one-size-fits-all solution. It is a multifaceted disease which will require continual advancements in therapy and pharmacology. But, we will also require advancements in the social awareness of this disease and to challenge the stigma that drug abuse is a choice rather than compulsion and that they are entirely to blame.

References

Arbor,A (2010, Sep 10): The tempted brain eats: Pleasure and desire circuits in obesity and eating disorders - PMC.

Koob, G. F., & Volkow, N. D. (2016, August). Neurobiology of addiction: A neurocircuitry analysis. The lancet. Psychiatry. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6135092/ - Provided image

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023, September 25). Treatment and recovery. National Institutes of Health. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/treatment-recovery

Kumar, R. (2024, June 8). Buprenorphine. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459126/

Sayin, H.U., 2019. Getting high on dopamine: Neuro scientific aspects of pleasure. SexuS J, 4, pp.883-906. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Umit-Sayin/publication/333617480_Sayin_HU_Pleasure-High-on-Dopamine_A_Multidisciplinary_Academic_Journal_Published_Quarterly_by_CISEATED-ASEHERT_www_SAYIN_HU_Getting_High_on_Dopamine_Pleasure_SexuS_Journal_4_11_883-906_MARCH_Part-1_G/links/5cf732ef299bf1fb18597e6c/Sayin-HUe-Pleasure-High-on-Dopamine-A-Multidisciplinary-Academic-Journal-Published-Quarterly-by-CISEATED-ASEHERT-www-SAYIN-HUe-Getting-High-on-Dopamine-Pleasure-SexuS-Journal-4-11-883-906-MARCH-Pa.pdf

Sonne, J., Reddy, V. and Beato, M.R. (2022). Neuroanatomy, Substantia Nigra. [online] PubMed. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536995/#:~:text=The%20substantia%20nigra%20is%20a.

Berridge, K.C., Ho, C.-Y., Richard, J.M. and DiFeliceantonio, A.G. (2010). The tempted brain eats: Pleasure and desire circuits in obesity and eating disorders. Brain Research, 1350, pp.43–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.003.

Calabrò, R.S., Cacciola, A., Bruschetta, D., Milardi, D., Quattrini, F., Sciarrone, F., Rosa, G., Bramanti, P. and Anastasi, G. (2019). Neuroanatomy and function of human sexual behavior: A neglected or unknown issue? Brain and Behavior, [online] 9(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1389.

Yu, Y., Miller, R. and Groth, S.W. (2022). A literature review of dopamine in binge eating. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00531-y.