- Mar 2, 2025

The Evolution of Surgery

- Saumya S and Husniddin H

- Medicine, Technology

- 0 comments

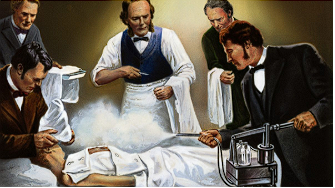

Surgery is often perceived as a daunting experience, whether you've undergone it before or not. The thought of being under the knife can evoke anxiety and fear in many. However, the incredible advancements in surgical techniques and medical technology have transformed this perception. Today, surgeries are more precise, safer, and less invasive than ever before. With these innovations, the once daunting prospect of surgery is now something that should inspire confidence rather than fear. But it wasn’t always like this: surgical procedures have had a long and complex evolution which has taken more turns for the better and the worse. We’ll be exploring said evolution, as well as looking at how it has shaped surgical practice today.

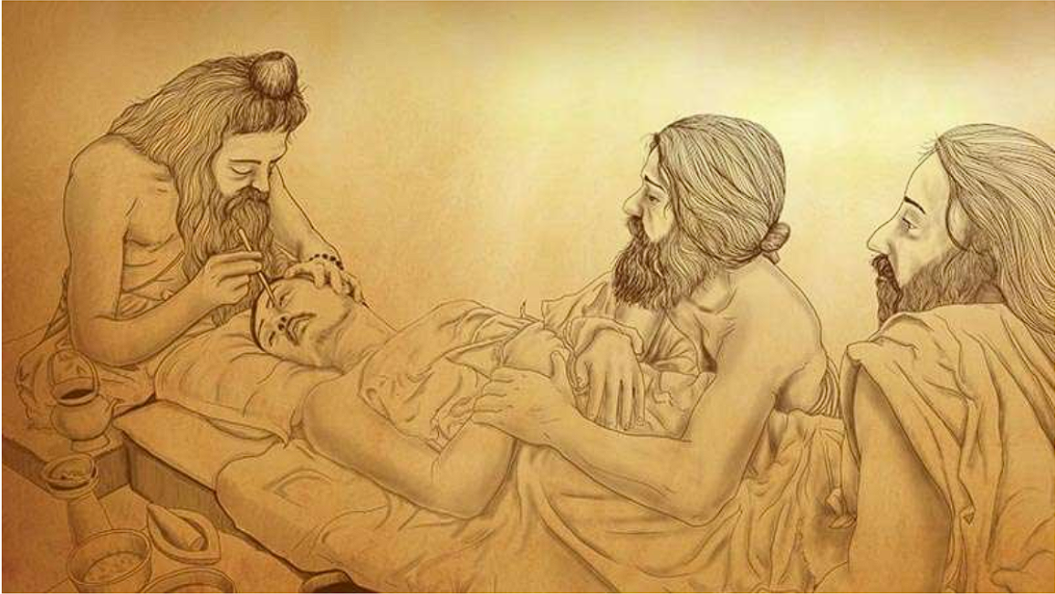

We start in India, with the visionary Sushruta Samhita (literally Sushruta’s Compendium). Written around 600 BCE, it describes in an almost all-encompassing way all of the basic principles of surgery from planning and precision to specific aspects such as haemostasis. Sushruta performed early versions of rhinoplasty and otoplasty (facial plastic surgery) and if that wasn’t enough pioneered orthopaedics with his detailed account on treating 12 types of fracture and 6 kinds of dislocation, leaving modern surgeons reading through his work stumped. Perhaps most surprising, however, is how he approached the teaching of surgery and medicine: he made his students take a solemn oath (often compared to the Hippocratic Oath) and also was an early promoter of using dissections as a way to learn human anatomy. The Sushruta Samhita remained confined Hindu religious practice for over a millennium after his death: the first translation into a different language took place in the eighth century AD into Arabic as ‘Kitab-i-Susurud’ deep into the Islamic Golden Age.

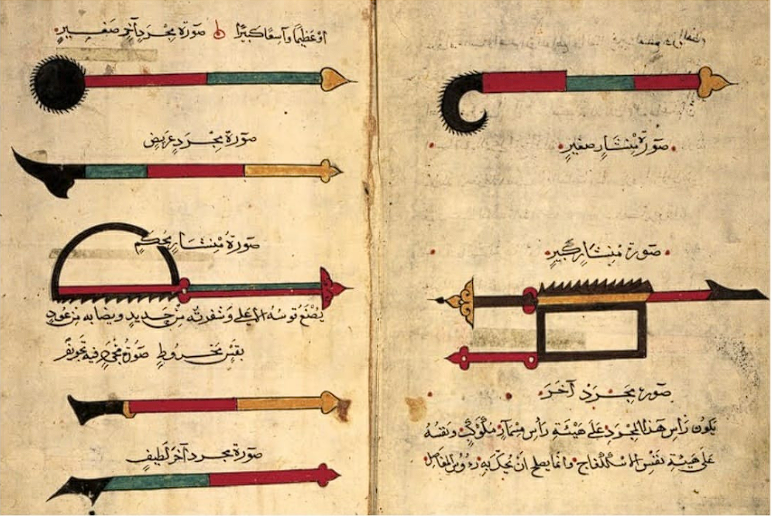

The Islamic Golden Age also heralded another one of the greats of pre-modern surgery - Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi, better known as Abulcasis. Based in Muslim Spain, he authored the huge 30-book medical encyclopedia Kitab al-Tasrif, of which the very final book On Surgery and Instruments (written around 1000 CE) became a key authority in European universities of the time such as Montpellier. It was essentially the very first illustrated surgical guide ever written, providing detailed diagrams of a range of surgical instruments (some of which, such as double hooked instruments, were unheard of before him and were invented by him) as well as applications of where to use them in different treatments. Within the text we can also find plenty of procedures that have been misattributed to later European physicians and doctors, such as Kocher’s method of treating a dislocated shoulder and the Walcher Position in pregnancies. It’s not a surprise then that when the final book was translated into Latin in the 12th century, it became a standard book in major medical universities and contributed to many further discoveries, even if without attribution.

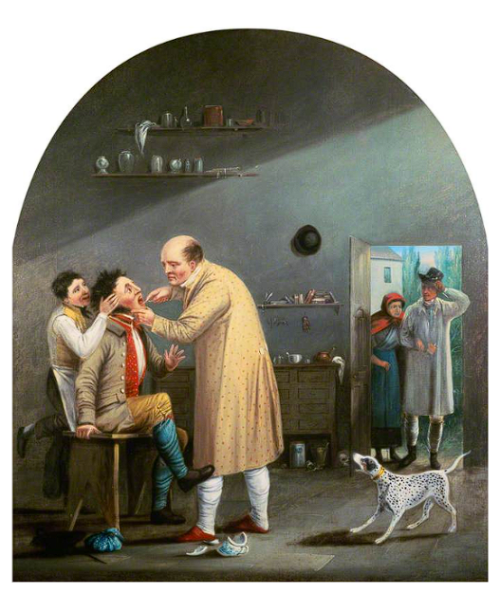

In stark contrast, surgical practices weren’t exactly performed by religious clerks in the case of Sushruta or great polymaths like al-Zahrawi in medieval Europe. In fact, surgery took place in the unassuming venue of the barbershop, where skilled apprentices would essentially do the dirty work (physicians saw themselves as ‘above’ the practice) in filthy conditions and without any medical knowledge. The result? Incredibly high surgical mortality, to the point that it was probably more dangerous to go to the doctor to get yourself treated than to suffer the disease itself. Even then however, the minority that did combine surgery and medicine were highly influential, such as the French surgeon and physician Guy de Chauliac. While he also wrote a massive medical encyclopaedia on surgery (we’re beginning to see a pattern here, aren’t we?), that probably wasn’t what he should be remembered for. In fact, he was the only major surgeon to not flee his city upon the arrival of the bubonic plague and instead attempted to provide treatment for its victims, supposedly curing himself of the disease and being the chief medical advisor in the Papal court.

As the Renaissance started to bloom into the early modern era in Europe, more influential figures became prevalent in the field contributing more and more inventions and discoveries. French army doctor and barber-surgeon Ambroise Pare built on the foundations of al-Zahrawi’s work on the ligature of arteries in al-Kitab al-Tasrif, discovering the inefficacy of the common practice of using hot irons to cauterise wounds and close blood vessels. German surgeon Wilhelm Fabry and his wife Marie Colinet pioneered amputation for gangrene and the Caesarean section respectively, although once again building on al-Kitab al-Tasrif. A particularly infamous example from a few hundred years later would be the Scottish scientist John Hunter. He was the inspiration for the famous novella Jekyll and Hyde, and the trade of grave-robbery examined thousands of specimens of human organs, bodies and even foetuses (and most likely was involved in the murder of many). Despite this, his importance cannot be overstated: he laid the foundations of scientific investigation through his experiments and greatly advanced understanding of surgical techniques informed by the anatomy. The Hunterian Museum in London, of which a part is pictured above, holds many of his specimens which he examined.

However, up until this point, one crucial part of surgery was overlooked. Antiseptic and aseptic technique is crucial in surgery as it ensures that the surgery actually takes place to improve the condition of the patient, not worsen it, yet it was ignored with primitive excuses such as ‘bad air’ or ‘devils’. The man to change that would be Joseph Lister. Through his work in numerous hospitals, he noticed (initially through the observation of Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis) that medical students were causing deaths in the maternal ward due to a lack of handwashing after they took part in an autopsy. As a result, he used carbolic acid to disinfect instruments and kick-started all of the vital practices of antisepsis that are used in hospitals today: the use of gloves, regular handwashing (with more than just water) and the sterilisation of surgical instruments.

The 20th century was the time when scientific discovery took off in relation to previous eras. Just before the century’s advent, Wilhelm Roentgen discovered X-rays and their ability to penetrate their skin, and that wasn’t all. In 1901 Karl Landsteiner discovered the 4 blood types allowing for blood transfusion to be pioneered in 1914. Open heart surgeries started in 1925, hip replacement in 1940, kidney transplants in 1954 and heart-lung transplants in 1987. In 1998, stem cell therapy, the rather dystopian method of re-engineering bodily tissue using undifferentiated cells (allowing for cloning of body cells), and by the time the 21st century began, even robotics entered surgery with the ZEUS robotic surgical system in 2001, which performed the first remote surgery.

Well, now that we’re in the present, let’s have a look at some standard medical steps taken by a multidisciplinary team in preparation for a surgery. Prior to a surgery, after the medical team has decided, along with the patient, the best course of action for their condition, the patient has to fill in a consent form. The form contains information about the risks of the operation, risks if the patient decides to wait, the benefits, whether there are any alternate treatments, extra procedures that may become necessary during the operation, information about the anaesthetics that will be used, consent for the doctor to perform the surgery (and that it is not guaranteed a particular person will perform the procedure), and whether their medical information can be used for scientific research purposes.

After all the forms have been completed, the multidisciplinary team will review the patient information and optimise the patient for surgery at least 5-6 days prior to the surgery, although this may be different depending on the urgency and severity of the patient’s condition. This is known as the ‘Preoperative Assessment’. Any necessary tests are conducted on the patient to plan the surgery accordingly. This includes getting information about their medical history and any current medical problems such as diabetes, asthma, lung and heart problems, and blood pressure. Information about whether the patient smokes, drinks alcohol, abuses other substances, whether they are overweight, or if they have any allergies, is also needed. All of this is crucial for planning the right anaesthetics for the patient. (To learn more about Anaesthetics, check out this article: https://www.ethnostemm.com/blog/the-anatomy-of-agony )

Common Ethical Dilemmas a surgeon may face before, during, or after a surgery include:

Whether they should start, continue or stop treatment for a patient (especially for end-of-life treatments). This has to do with beneficence and non-maleficence. Should the doctors perform surgery on the patient, which would cause them a lot of pain and not help them a lot, or is it better to not do the surgery and let the patient go in peace?

If something goes wrong during surgery, they must make a quick decision on what to do (for example, when doing surgery on a pregnant woman, something goes wrong, and the surgeon has to choose between saving the baby or the mother, but the mother has said to save the baby and not her previously)

Choosing between ‘over-treatment’ and ‘under-treatment’, while also considering the efficiency and use of the hospital’s limited resources.

Pressure from a patient or family to do a surgery even if the doctors know and have said it is unlikely to help.

Creating an informed consent form and making sure the patient is making a personal decision and is capable of doing so.

After all this, the patient may have to take drugs to thin their blood and/or take blood-pressure pills, and they may be required to not eat or drink anything for a certain time-period before the surgery. Most importantly, they need to relax before the surgery.

The multidisciplinary team will plan the surgery carefully according to the patient’s requirements, preparing for all types of scenarios. The doctors will need a good night’s sleep the night before, eat healthy food, and avoid caffeine and exercise, as this can cause tremors in their hands.

On the morning of the surgery, the multi-disciplinary team will have a brief discussion about the procedure and confirm everything is ready, after which the doctors will then scrub their hands and gown, keep a calm mind, and do a successful surgery!

After the surgery, the patient will be moved back to the ward or waiting room, and the patient and their family will be told how the surgery went. The patient may feel groggy due to the lingering effects of general or local anaesthetics. A nurse may give the patient oxygen through tubes or masks. The patient’s blood pressure and temperature will be taken regularly. To avoid blood clots, the patient will be encouraged to move around, or even just do some leg exercises. If required, the patient may also be offered a rehabilitation programme.

Before being discharged from the hospital, the patient will have an appointment with a physiotherapist, who will recommend specific exercises to ensure complete recovery, and if all goes well, the patient will be discharged and will begin their journey of getting back to normal.

New technological advancements in surgical equipment

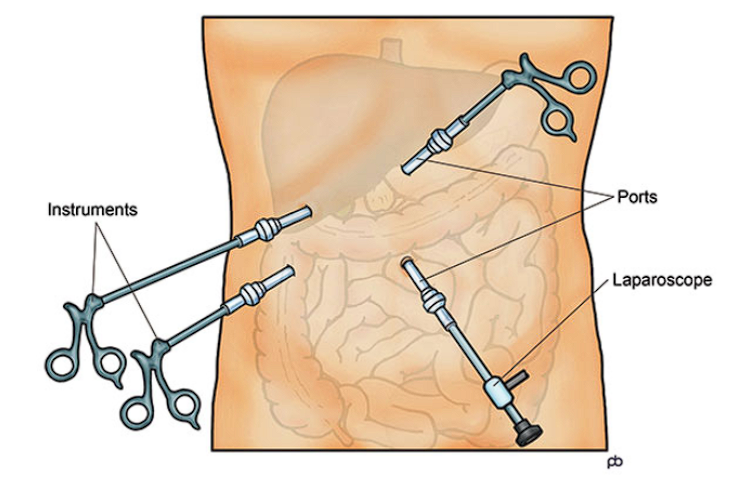

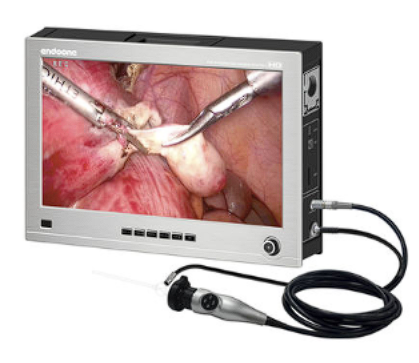

Keyhole Surgery: Minimally invasive surgery. Small ‘keyhole’ incisions act as a port of medical instruments during a surgery. They can be as small as half an inch long, or even less.

Robotic Surgery: A form of minimally invasive surgery that uses robotic arms to conduct precise surgeries through a keyhole. A surgeon operates the robotic arm from a console.

Endovascular Surgery: Threading a tiny catheter (a surgical tube that drains urine from the bladder) through a blood vessel and then doing the operation through it. Surgeons use a guidewire to pass the surgical instruments through, then remove the wire. This minimises bleeding

Endoscopic Surgery: A narrow tube with a lighted camera at the end is inserted inside the body through an already existing hole such as the nose or mouth, or through an incision like a keyhole. Surgeons operate through these endoscopes.

A laparoscopic surgery: A small cut (keyhole) is made near the belly button, and carbon dioxide is injected to inflate the abdomen. A thin, lighted tube with a camera is then inserted through the incision to view images of organs or perform surgery.

-

Other common medical equipment used in preparation for/during surgery: X-Rays, PET scans, MRIs, Ultrasounds, Radiography, CT Scans, and many more.

Surgery has come a long way, with many new technological developments and findings, but this has also led to some ethical dilemmas, and therefore doctors have to make tough decisions every single day. To make sure a surgery is done ethically correctly through the use of AI and technology, a surgeon must turn to the 4 pillars of Medicine: Autonomy, Beneficence, Justice, and Non-maleficence.

Some of ethical dilemmas related to technology that we should be aware of include:

Protection of patient confidentiality and privacy: there may be conflict between economic interests and the principle of beneficence (doing good for patients). Although it is cost-efficient and quick, the electronic transmission of crucial and private medical data could cause autonomy and confidentiality to be breached. This is likely to become more common in the future as telemedicine and cybermedicine become more widely used. Breach of personal data can lead to ‘personal humiliation, loss of reputation, and risk to financial status’. (“Ethical Dilemmas of the Practice of Medicine in the Information Technology Age,” n.d.)

The use of Artificial intelligence and relying on it to diagnose a patient and plan treatments: many people are ‘worried over the extent of physician reliance on machine intelligence’, making us question their competencies.

Data Ownership: how is data obtained from patients through wearable devices and digital health apps, stored and shared, and should patients have greater control over this? Should there be newer, clearer policies and consent mechanisms for data sharing, patient’s right to access and control their data?

Surgery in the future is likely to become even more precise and less-invasive, especially with the use of robotics, as this reduces the chances of human error and a robot-arm is much less likely to tremor. In the future, it is also more likely for remote surgical procedures to happen, wherein a surgeon sitting in the UK could perform a surgery in Egypt (pretty cool, right?)

Yes, as more technological advancements are made, more ethical dilemmas will also arise, but that is also the beauty of medicine and being a part of a medical team, such as a doctor. It is us, humans, that have taken us so far and made so many new developments. Humans are also the only animals that seem to have a sense of morality, and so no matter how advanced AI may get, emotional, and morally and ethically right decisions are something only a human doctor can achieve.

References

Fn, J. W. R. M. (2024, April 15). The historical timeline of surgery. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/the-history-of-surgery-timeline-3157332

Anatomy in Ancient India: a focus on the Susruta Samhita. National Library of Medicine https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3039177/

Sushruta: the father of surgery. National Library of Medicine https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5512402/

https://www.heritagetimes.in/father-of-modern-surgery-al-zahrawi

Karagِzoğlu, Bahattin (2017). Science and Technology from Global and Historical Perspectives. Springer. p. 155."This last volume is a surgical manual describing surgical instruments, supplies, and procedures. Scholars studying this manual are discovering references to procedures previously believed to belong to more modern times."

Shevel, E; Spierings, EH (April 2004). "Role of the extracranial arteries in migraine headache: a review". Cranio: The Journal of Craniomandibular Practice. 22 (2): 132–6.

McGrew, Roderick (1985). Encyclopedia of Medical History. New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 30–31.

Dubner, Stephen J. and Levitt, Steven (2009). Superfreakonomics.

HT_0709_consent 1. (n.d.). Consent Form 1. https://hgs.uhb.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/Consent20Form201.pdf

Preparing for an operation. (n.d.). The Royal College of Anaesthetists. https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/documents/anaesthesia-explained/preparing-operation

Website, N. (2024, July 12). After surgery. nhs.uk. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/having-surgery/afterwards/

Ethical dilemmas of the practice of medicine in the information technology age. (n.d.). Singapore Med J 2003, Vol 44(3) : 141-144. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=d71aeda90ac2b6461a1641c6c0d9a1a177aa1e23

Ethics challenges shape patient care and Surgeon Well-Being. (n.d.). ACS. https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/news-publications/news-and-articles/bulletin/2023/october-2023-volume-108-issue-10/ethics-challenges-shape-patient-care-and-surgeon-well-being/#:~:text=Ethical%20Issues%20in%20Clinical%20Surgery%20identifies%20six%20core%20themes%20that,the%20expectations%20of%20the%20authors.

Website, N. (2024b, July 12). After surgery. nhs.uk. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/having-surgery/afterwards/

Professional, C. C. M. (2024, October 22). Minimally invasive surgery. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/procedures/minimally-invasive-surgery

Laparoscopy. (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/laparoscopy/#:~:text=What%20is%20a%20laparoscopy?,traditional%2C%20%22open%22%20surgery.

IMAGE LINKS:

https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/w800h800/collection/CDN/WELL/CDN_WELL_L_16047-001.jpg

https://www.heritagetimes.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/92C0B95B-A435-4032-9007-76865F00D1BB.jpeg

https://hips.hearstapps.com/hmg-prod/images/gettyimages-515351938-1512320813.jpg?resize=640:*